I grew up knowing my Spanish side—the stories, the language, the lineage preserved and passed down. But my Indigenous roots, remained largely silent. The only inklings would be comments about my relatives complexions. Like so many descendants of colonization, I inherited an asymmetry: one ancestry loud and documented, the other severed from me by deliberate erasure. This poem is part of my process of decolonizing, of reconnecting.

Nahuatl isn’t a dead language—about 1.7 million people speak it today across Mexico. It’s alive, evolving, thriving in communities that never stopped speaking it. My disconnection isn’t because the language or culture disappeared; it’s because colonization severed my family’s connection to it. Learning Classical Nahuatl, studying the codices, working with these forms of expression—it’s not about resurrecting something lost. It’s about reconnecting to something that continues, something I was kept from. It’s asking: what do my relatives still know? How do Nahua people see the world? What songs are still being sung?

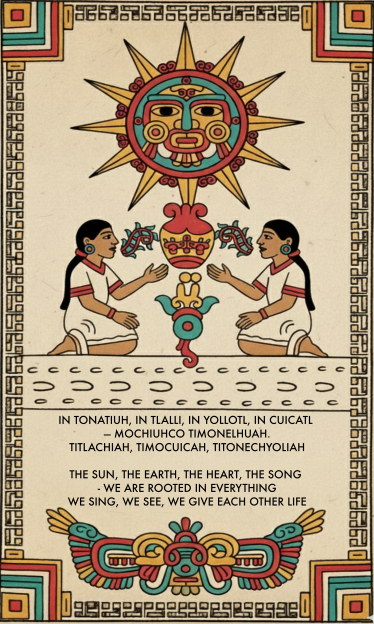

I’ve been working on a piece that brings together language, image, and meaning in ways that connect historical and contemporary Nahua thought. The result is a short poem in Classical Nahuatl paired with a digitally drawn image that speaks to themes of reciprocity, rootedness, and mutual life-giving.

The Language

For the visual piece, I turned to the Visual Lexicon of Aztec Hieroglyphs, a very helpful resource that catalogs pictographic elements from Aztec codices. I also consulted Deciphering Aztec Hieroglyphs: A Guide to Nahuatl Writing (and this helpful associated video ) which provided broader context and useage of the language.

From what I have learned, Classical Nahuatl was not written with a full alphabet or syllabary. Instead, the Mexica used a pictorial-semantic writing system, a mix of logograms, pictographs, and occasional rebus elements. This system was not designed to record full spoken Nahuatl word-for-word.

Nahuatl writing was used heavily for record-keeping, naming, calendrics, and state administration, while the deeper cultural knowledge—stories, songs, poems, ritual speeches, and moral teachings—remained rooted in a rich oral tradition.

Working in Classical Nahuatl meant thinking carefully about verb forms and how they carry meaning. The poem uses first-person plural forms throughout – timonelhuah (we are rooted), titlachiah (we see), timocuicah (we sing)—and crucially, titonechyoliah (we give each other life). That final verb uses a reciprocal construction (to-) that grammatically encodes the mutual nature of the action. We don’t just give life; we give life to each other. The language does philosophical work.

The poem follows the Nahuatl poetic tradition of difrasismo—paired concepts that together create deeper meaning. Tonatiuh-tlalli (sun-earth) represents the cosmos. Yolotl-cuicatl (heart-song) echoes the famous in xochitl in cuicatl (flower and song), the Nahuatl expression for poetry, truth, and beauty.

The Image

The composition came together as a kind of modern codex page: Tonatiuh (the sun) – Prominently at the top, radiating life-giving energy. Tlalli (the earth) – The ground from which the xochitl (flower) showing rootedness in the earth. The two figures facing each other in reciprocal communion embody “we give each other life” – their gestures suggest exchange, dialogue, and mutual animation. Cuicatl (song) – coming from the figures mouths. The central symbol between them, the yollotl (heart, life).

What struck me in working with these glyphs is how much they already contain the concepts I was trying to express. The symmetry, the facing figures, the way hands reach toward shared symbols—these visual conventions encode reciprocity and relationship. I wasn’t inventing a new visual language; I was learning to speak in one that’s been expressing these ideas for centuries.

Pronounciation

In tonatiuh, in tlalli, in yollotl, in cuicatl — mochiuhco timonelhuah. een toh-NAH-tee-oo, een TLAH-lee, een YOH-lohtl, een KWEE-kahtl — moh-CHEE-ooh-koh tee-moh-NEL-wah

Titlachiah, timocuicah, titonechyoliah. tee-tlah-CHEE-ah, tee-moh-KWEE-kah, tee-toh-neh-choh-LEE-ah

Key pronunciation notes:

- tl = one single sound, not “t” + “l” separately

- hu = “w” sound (like English “w”)

- cu/qu = “k” sound (like English “k”)

- ch = like English “ch” in “church”

- Stress usually falls on the second-to-last syllable (shown in CAPS)

- All vowels are pure: a=”ah”, e=”eh”, i=”ee”, o=”oh”

Grammer Guide

In tonatiuh, in tlalli, in yollotl, in cuicatl — mochiuhco timonelhuah.

in = definite article “the” (repeated before each noun for emphasis)

tonatiuh = “sun, the sun deity”

- Root: tona- “to shine, to be warm”

- -tiuh = agentive suffix “the one who does X”

- Literally: “the one who shines/warms”

tlalli = “earth, land, soil”

- Basic noun root tlal- “earth”

- -li = absolutive noun ending

yollotl = “heart, life, life-force, soul”

- Root: yol- “to live”

- -otl = noun suffix

- The heart was the center of life and consciousness in Nahuatl thought

cuicatl = “song, poem”

- Root: cuica “to sing”

- -tl = absolutive noun ending

- Poetry and song were inseparable concepts

mochiuhco = “in everything”

- mochi = “all, everything”

- -co = suffix, locative “in, at, within”

timonelhuah = “we are rooted, we root ourselves”

- ti- = 1st person plural subject “we”

- -mo- = reflexive prefix “ourselves”

- nelhua = verb stem “to root, to take root, to be founded”

- -h = plural marker (makes it “we” not “you singular”)

Titlachiah, timocuicah, titonechyoliah.

titlachiah = “we see, we behold”

- ti- = 1st person plural “we”

- tla- = indefinite object prefix “something/things”

- chia or itta = verb stem “to see, to look at”

- -h = plural marker

timocuicah = “we sing”

- ti- = 1st person plural “we”

- -mo- = reflexive (here it intensifies: “we sing ourselves”)

- cuica = verb stem “to sing”

- -h = plural marker

titonechyoliah = “we give each other life, we animate/enliven one another”

- ti- = 1st person plural “we”

- -to- = reciprocal prefix “each other, one another”

- -nech- or -tech- = object marker (in this reciprocal context)

- yolia = verb stem “to live, to give life to, to animate”

- -h = plural marker

Note: The reciprocal construction with -to- creates the “each other” meaning, making this a mutual action

Performance

Nahuatl poetry was never meant to be read silently. Cuicatl means both “poem” and “song”—they were the same thing. This piece is designed to be sung or chanted, ideally by multiple voices in call-and-response or as a layered community chant. The reciprocal grammar demands reciprocal breath.

I’m still working out the musical setting, but the rhythm of the language itself suggests a steady drum pattern, the kind that would have been played on a teponaztli or huehuetl. The repetition of phrases, the building intensity—it all points toward performance as ritual, as shared action rather than individual consumption.

What I’m Learning

This project has taught me that working in Nahuatl isn’t just about translation—it’s about letting the language reshape how you think. It’s agglutinative structure, where prefixes and suffixes build complex meanings, means that concepts like reciprocity and reflexivity aren’t add-ons; they’re built into the architecture of expression.

Similarly, working with codex imagery isn’t about decoration. These visual forms carry philosophical content. When two figures face each other across a shared symbol, that’s not just an aesthetic choice—it’s a statement about how life and meaning emerge through relationship.

I’m grateful for resources like the Visual Lexicon of Aztec Hieroglyphs website that make this work accessible while maintaining respect for the source material (which is not easy to decipher). And I’m humbled by how much these old forms still have to teach us about reciprocity, rootedness, and the ways we give each other life.

Decolonizing the Mind, Reclaiming Wholeness

This work—learning Nahuatl, creating with codex imagery, singing reciprocal songs—is part of a larger practice of decolonization. Not just decolonizing my family history or reclaiming a severed heritage, but decolonizing the very ways I think, create, and relate to the world.

White supremacy culture, as Tema Okun has documented, operates through characteristics like individualism, binary thinking, perfectionism, and a worship of the written word over other forms of knowing. These aren’t neutral cultural preferences—they’re the residue of colonialism, designed to value certain ways of being (linear, individualistic, competitive) while devaluing others (cyclical, communal, reciprocal).

Western education has trained us to be profoundly left-brain dominant. As neuroscientist Dr. Jill Bolte Taylor explains, we’ve elevated the left hemisphere’s values—individual identity, linear time, hierarchical categorization, acquisition—while suppressing the right hemisphere’s wisdom about interconnection, presence, and our fundamental unity with all life. The left brain says “me and mine and I want more.” The right brain knows “we are one construct”

Working with Nahuatl reopens those suppressed ways of knowing. The language itself resists left-brain dominance: its agglutinative structure builds meaning through relationship and context rather than rigid categories. The reciprocal verb forms—titonechyoliah (we give each other life)—grammatically encode interdependence. You can’t even conjugate the verb without acknowledging that life doesn’t flow one direction; it’s mutual, cyclical, relational.

The codex imagery does similar work. These aren’t just “decorative” or “symbolic”—categories that reduce Indigenous visual knowledge to something less-than alphabetic writing. They’re a complete system of communication that engages spatial thinking, color relationships, and embodied knowledge. Working with these forms exercises parts of my brain and ways of knowing that colonial education systematically atrophies.

This is what I mean by cultural diaspora and grounding. I’m not romanticizing a lost past or trying to “return” to something. I’m recognizing that colonization didn’t just sever my family from Nahuatl—it severed all of us from more holistic, relational ways of being in the world. Learning the language, creating with the glyphs, singing the songs: these practices literally rewire neural pathways, moving me toward the right hemisphere’s truth that we are interconnected, that I am because we are, that life is mutual animation.

In tonatiuh, in tlalli, in yollotl, in cuicatl — mochiuhco timonelhuah.

We are rooted in everything. Not as isolated individuals extracting resources, but as parts of a whole, giving each other life. That’s not just poetry—it’s a different ontology, a different way of being human. And it’s been here all along, waiting to be remembered.